In this post I will provide a blueprint for building your own serverless platform, based on the lessons learned from working on Auth0 Extend in the recent years.

Why would you want to build a serverless platform?

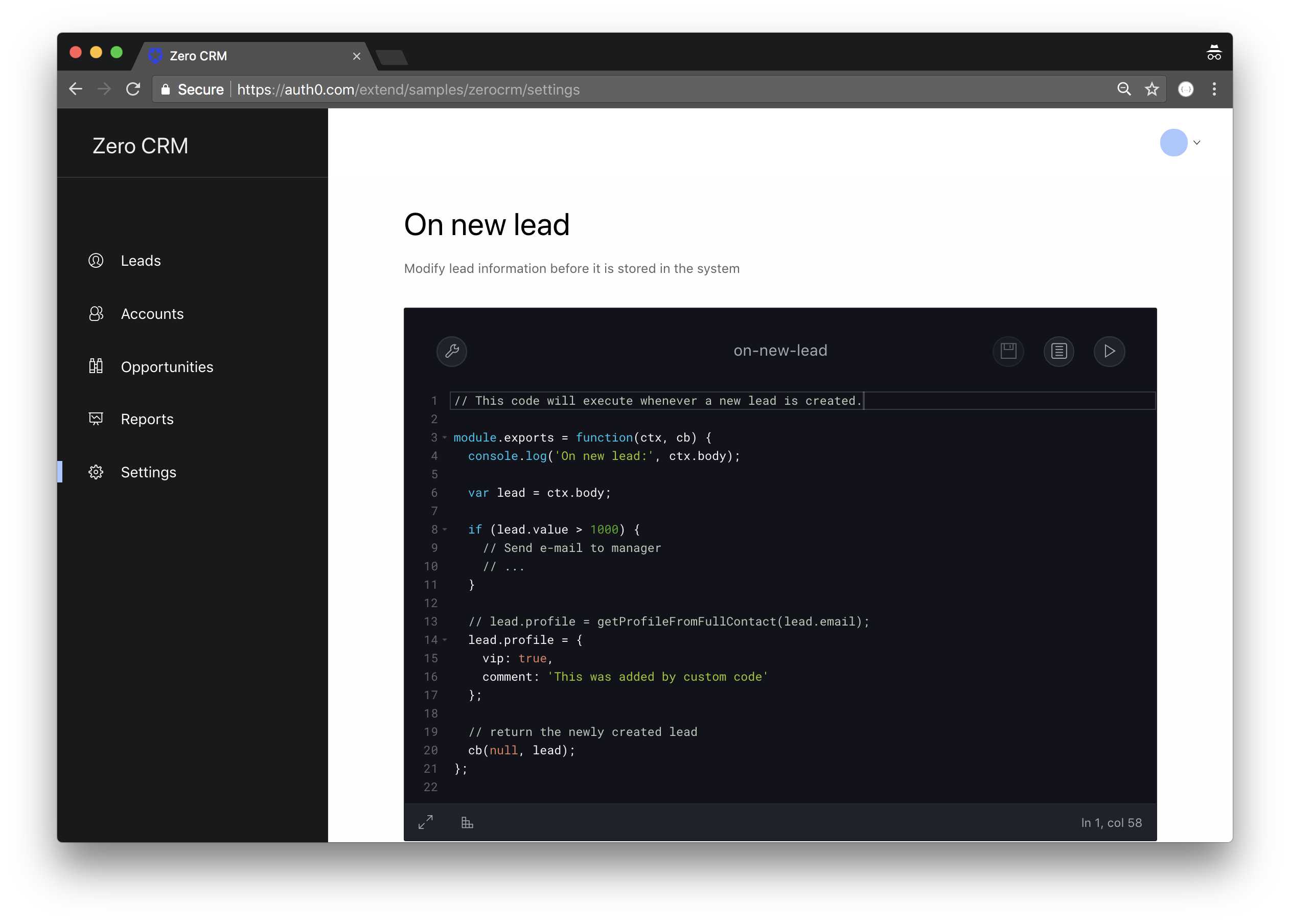

The serverless (Function-as-a-Service) computation model is a powerful complement to the webhook-based extensibility of a SaaS platform.

In the previous post I proposed that Serverless webhooks will revolutionize the SaaS by removing friction from customizing SaaS platforms and integrating external systems.

Serverless webhooks benefit end users, sales teams, and ultimately make the SaaS platform more successful.

A growing number of SaaS platforms embrace the serverless webhook model. Twilio Functions and Netlify Functions are two recent examples.

If you want to enable the serverless webhook model in your SaaS, you may be considering building your own serverless platform to support it. The rest of this post provides one design informed by the experience of building Auth0 Extend.

Requirements

In order to complement a webhook-based extensibility model of your SaaS product, your serverless platform will need to meet this minimum set of requirements:

- It must offer a core concept of a function as a unit of custom business logic that runs when a webhook in your SaaS platform is triggered.

- It must support adequately rich programming environment. In this post, I will assume that Node.js with the ecosystem of all public NPM modules (over 500k) is sufficient.

- It must offer an API surface that allows managing functions as individual webhooks.

- When a webhook event is triggered in your SaaS platform, you must be able to execute the corresponding function to handle the webhook HTTP request.

- The serverless platform must provide a mechanism to isolate the execution of functions of eache tenant, since each tenant can author their own set of functions with untrusted and potentially malicious code.

- The latency of execution of your serverless webhooks must be acceptably small and predictable. In particular, the cold and warm latency cannot vary too much - this is particularly important if they execute as part of a UI interaction with the end user of your SaaS.

In practice, your specific scenario may have many more requirements. The design blueprint in this post only addresses the ones above.

Let’s start designing a serverless platform from the bottom up. We will use basic building blocks so that the design is relatively easy to port to a variety of environments.

Compute

Execution of functions requires basic computing resources: CPU, memory, disk, and network. We will then start with an empty VM.

We will tackle scalability later. Right now let’s focus on the components running within the VM.

Proxy

Serverless webhooks as well as APIs that allow their management are both exposed over HTTP. HTTP endpoints will be the main entry into the functionality of our VM, and an HTTP proxy is a component that will decide how to process a particular request.

You can use a variety of technologies for the proxy: HAProxy, Nginx, all the way to writing your own.

Management APIs

At a minimum, the management APIs of our serverless platform need to allow for basic CRUD operations on serverless webhooks. You need to be able to create, update, read, delete, and list available webhooks. So you need a specialised web server component implementing these APIs. The proxy must be able to route the management API requests to this component.

Management APIs themselves are stateless. Any durable representation of a serverless webhook, most notably its code, must be stored outside of the context of this component.

Persistent storage

Persistent storage is required to maintain any durable state representing a serverless function. At a minimum, this is the code of the function itself with a manifest of module dependencies. Depending on your scenario, this state may also include additional configuration that the code requires at runtime, like API keys, connection strings, or other metadata that controls the execution of the function.

The essence of the Function-as-a-Service paradigm is that individual functions are small units of business logic, unlike large monolithic web apps of the days past. Many standard databases or storage solutions should be a good fit to store this data. MongoDB, DynamoDB, MySQL should all fit the bill.

Now that you can manage your serverless functions via HTTP APIs, let’s move on to the interesting part - executing them with low latency and adequate isolation.

Execution model: the theory

While you could say that every function is running completely isolated from other functions, it is beneficial to introduce a level of indirection.

Consider a concept of a container which denotes an isolation boundary for executing code. Any two functions running in distinct containers are guaranteed to be isolated, while any two functions running within the same container may, in fact, share the same process, address space, and therefore in-memory state. Such design has enough flexibility to support the isolation needs of a multi-tenant SaaS platform, at the same time enabling optimizations across serverless webhooks of a single tenant.

Let’s then assume a model in which several serverless functions can be grouped together to run within the same isolation boundary of a container. They can share the state with one another (e.g. DB connection pool) while maintaining logical isolation of the business logic. Such taxonomy of containers and functions must be supported by the management APIs described above, which is straightforward to solve. The interesting challenges lie in function execution mechanics.

So, let’s design it.

Execution model: the practice

An HTTP request arrives as a result of a webhook being triggered in your SaaS. In response, the serverless platform must run a Node.js function, and do so with low latency and adequate isolation from other functions.

Given such a request, a naive, CGI-like implementation would create an isolated execution environment, e.g. one using Linux containers and namespaces, or Windows job objects, with some additional measures of security applied on top. It would load the code of the function from the persistent storage, fetch the module dependency manifest, and provision those modules. It would then execute the function in this environment, return results to the caller, and clean up after itself.

This is a great story, especially that it affords the end user ample time to go to lunch and file their tax return.

In most scenarios, the latency introduced by the overhead of creating isolated execution environments for every request is not acceptable, even in the lightweight world of Linux containers.

One solution to this problem is to reuse containers to process multiple requests of the same tenant, similar to how FastCGI improved over CGI. Container reuse will reduce warm latency. To enable processing of multiple requests by the same container, the protocol over which these requests are passed to the container must be defined. It is convenient for that protocol to be HTTP, as that will allow the VM-level proxy to simply reverse proxy serverless webhook execution requests to the container associated with the tenant who wrote the serverless webhook.

In order to pull this design off, we need a component that will manage the lifetime of the containers and their association with a specific tenant. Let’s call this component a container handler.

When a request to execute a specific serverless webhook arrives at the proxy, the proxy consults the container handler to obtain the address of the specific container that should handle this request. If a container assigned to a specific tenant is already running, the container handler promptly returns its address to the proxy which will in turn reverse proxy the request to that container.

A problem will arise when the proxy receives a request that needs to execute in a container that is not yet running. In this case, the container handler creates a new container and provision the requested serverless function within it based on the data in the external storage. This can incur a substantial performance penalty.

Cold startup latency is one of the challenges of serverless platforms. How do you create lightweight, isolated execution environments and provision them with necessary components quickly?

We don’t want our cold startup latency to be substantially different from warm latency. Let’s go back to the drawing board.

Reducing cold startup latency, part 1

A lot of the work related to starting up a new container is generic and can, therefore, be front-loaded. Let’s have the container handler maintain a pool of pre-warmed containers ready to be assigned to tenants as necessary.

With this design, when a request arrives on behalf of a tenant that does not yet have a running container, the container handler picks up one unassigned container from the pool, assigns it to the tenant for life, and notifies the proxy where to route the request. We have now cut out a substantial part of the container initialization time from the cold startup path: the creation of a container, and starting up of a process that runs a mini-HTTP server within it.

What work still remains to be done in the cold startup path? The container handler must obtain the code of the serverless wehbook from Storage and provision it within the container, along with the module dependencies. Neither the function code or the module dependencies are known at the time the generic container is created, so they need to be provisioned lazily when a message arrives. Anyone implementing Node.js applications knows that the size of the module dependency closure (the overall size of the node_modules directory) can grow rather quickly and adversely impact provisioning time.

We are not done with the cold startup latency problem yet. How do we solve the module provisioning problem?

Reducing cold startup latency, part 2

If reducing startup latency is an objective, running npm install to provision Node.js modules based on the dependency manifest of a serverless webhook while on the hot path of message processing is just an obvious no-go. The process can take arbitrarily long depending on how many modules need to be pulled from NPM and whether any build steps are necessary.

Doing so during serverless webhook provisioning via the management APIs will be a much more acceptable solution, as development usually has less strict latency expectations compared to the runtime. Given that, we are going to front-load building of the module dependency closure of a serverless function by executing it during the management API call that creates the function. This is great, but there is more.

Another interesting aspect of this problem is related to duplicated effort. If several functions have a dependency on the same module, will we really need to build this module anew each time? After all [email protected] is [email protected] is [email protected], regardless how many serverless functions depend on it. So let’s try to come up with a design that further optimizes around reuse of pre-built Node.js modules across different serverless webhooks, even when they are created by different tenants.

When a management API is called to create or update a serverless webhook, its module dependencies are inspected. For each dependency (e.g. [email protected]) that is not yet available in Storage in a built form, the management API schedules it to be built with the module builder.

The module builder is a background worker process running on a separate VM that will receive its work through a queue mechanism using technologies like AWS SQS, RabbitMQ, or similar. Its job is to receive a module build request, run npm install to build this module in the same environment in which it will eventually be used at runtime, capture the entire, built dependency closure (the entire node_modules folder), tar, zip, and put in Storage.

Since every module is considered for building individually, every version of every module will only be built once in the system as a whole. Given that, over time the latency of creating serverless webhooks via the management APIs becomes negligible, since all common module dependencies have already been built before.

At runtime, when the container handler prepares an unassigned container for execution of a specific serverless webhook, it first obtains the code of the function from Storage and then proceeds to provision modules the function depends on. This is done by obtaining the pre-built modules from Storage, unpacking them on the local volume on the VM, manufacturing a synthetic node_modules directory with symlinks to the read-only filesystem holding the physical module on the host, and attaching a volume with this directory to a specific container. This makes all module dependencies available to the serverless webhook code running within the container.

The added benefits of storing pre-compiled modules on the host VM’s filesystem and sharing them read-only with all containers and functions that require them include:

- reduction of storage requirements,

- reduction of network bandwidth to download the modules,

- and further reduction of cold startup latency.

For serverless webhooks for which module dependencies had already been downloaded by previously running functions, even by other tenants, the container handler does not even need to reach out to Storage.

With the design described above, warm and cold startup latency of serverless webhooks is very similar, which is an important consideration in a range of SaaS extensibility scenarios.

Scalability and reliability

What we have designed so far is a single VM solution that provides a self-contained, multi-tenant platform for managing and executing serverless webhooks. So what happens when they come, and the traffic explodes?

Given that one VM is self-contained and can function independently, you can accommodate increasing throughput by scaling out the number of VMs and putting a proxy in front of the cluster. If you use a flexible scaling technology like AWS’s Auto Scaling Groups, the size of the cluster can be dynamically adjusted as the load changes.

In the current design, the VMs are independent of each other. This is hugely helpful in increasing the overall reliability of the deployment. Lack of state shared between VMs means they can crash at any time (and they will, the frequency of which depends on your choice of specific technologies and the underlying platform) without affecting the remaining VMs. The Auto Scaling Group, or a similar solution, can subsequently replace a failed VM with a new one.

This reliability advantage has a drawback, however. A container for a given tenant may exist on every VM at the same time. If you want to support an increasing number of tenants running code concurrently, this can only be accommodated by scaling up - increasing the capacity of individual VMs in the cluster. This works up to a point - beyond a certain threshold of density you will need to consider adding smarts to the container handler component to be able to handle placement of a tenant’s container on just a subset of VMs in the cluster. This would require a technology to efficiently share a synchronized routing table data across the cluster, e.g. Zookeeper, etcd, or a similar solution. Such design is more complex and beyond the scope of this post.

Are we done yet?

Yes and no. After you have implemented the design above, you have a functioning, multi-tenant serverless platform that can power the serverless webhooks of your SaaS. Your CPO is happy. Your COO’s nightmare begins.

The system is up and running. The easy work is done. Now you need to run this system at 99.9…% availability, with 24/7 uptime, and zero-downtime upgrades.

The operations and devops of a serverless solution like the one described in this post is a project in itself, in many respects just as complex as the solution. Stay tuned for another post based on our experiences building and operating Auth0 Extend to those high operational standards.