Software teams fall into three categories with respect to the relationship between development and testing. Some are ignorant about testing to the extent of letting customers do it, and hence only have developer positions. Some consider the discipline split fundamental to the point of reflecting it in the organization structure or scope of job description. And some just know better.

I will describe my team’s transition from a structure (and culture) with separate development and test positions to a structure with only engineering positions. I will show measurable effects of this transformation as well as discuss subjective advantages and disadvantages of this transformation.

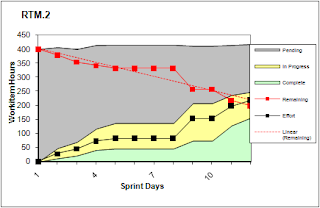

Once upon a time there was team of 10 brave men and women. There were 5 testers and 3 developers, each group with their own lead. The test and development leads reported to discipline managers, who in turn reported to a single cross-discipline manager. Given that a tester was 5 organizational clicks away from a dev, the team chugged along surprisingly nicely, cranking sprint after sprint in its little grassroots SCRUM process, painstakingly introduced a few months before (the larger organization is following the waterfall development model). Below is a snapshot of the burndown chart for one of these sprints:

I like SCRUM for several reasons. One of them is that it provides timely and insightful data about the quality of the process itself. A piece of wisdom that can be gleaned from the chart above is that the total number of work hours the team completed during the 2 week sprint is around 150. In this particular case 150 is also the number of hours the debt of the project was reduced by, since the planned work estimates remained rather constant throughout the sprint (at ~400 hour level). Given the entire team of 10 was declaring 100% availability during the 2 week sprint (equal to 80 hours per person in developed countries), the load factor for this sprint was a pathetic 18% (150/800). A load factor of 18% means that for every hour the team spends on the project, the remaining work is reduced by around 11 minutes. Compare this to the industry standard of 50% for experienced SCRUM teams (this team can be considered experienced having been using SCRUM for several months), and you can understand why project management thought there was room for improvement, to put it diplomatically.

After analyzing the underlying reasons for this suboptimal efficiency on the team, we have identified the following elements:

- Keeping development and test in sync within consecutive sprints was a loosing battle that consumed a lot of energy and coordination. Testers and developers had little incentive to help each other as they reported through management chains disjoint for the purposes of daily decision making.

- The split between developers and testers on the team introduced a need for unnecessary bureaucracy. Testers needed functional and design specs, a coded feature, and a written test plan to start implementing tests for the feature. Butts on both sides of the fence needed to be covered, and they were.

- Test team had no real incentive to optimize its processes. Test teams do not ship software, they write software that ensures the software that ships is of adequate quality. As such, a test team can be considered a cost center rather than a direct contributor to revenues. Therefore, a team created around a testing discipline has a conflict of interest built into it’s charter: if it strives to reduce the costs of shipping software by optimizing its processes, it will reduce it’s resourcing needs. Go figure what wins.

At this point there was a choice to be made. We could revert from using SCRUM painstakingly introduced several months earlier to follow the politically correct waterfall model practiced by the larger organization. That would relieve us from the necessity to look at the depressing performance data ever again, as such data was hard to come by in the waterfall process. Or we could bite the bullet and plunge further into the realm of organizational experimentation. Fighting hard the natural organizational survival instincts we chose the latter.

The proposal that was eventually put into practice was to have a team of engineers who do both development and testing as opposed to dedicated developers and testers. Furthermore, the engineers were reporting to a single lead as opposed to discipline specific leads. In order to test the hypothesis that such a change would increase efficiency, the team size was reduced by 50%, from 10 people to 5 people. The team continued to follow the SCRUM process.

Did I mention I like SCRUM because it helps measure the quality of the process? After the dust settled following the reorganization, we took another look at a burndown chart of the new team:

This burndown chart shows the status of the team a day before the end of a 2 week sprint, a few sprints after the reorganization. It is clear the team is on track to complete over 100 hours of work. Given that the planned work estimates remained largely constant, it can be assumed the project debt was reduced by 100 hours. The team was declaring 100% availability for the sprint, which gives us 25% load factor (100/400). It is still pathetic, but less so compared to the 18% before the reorganization. In fact, after another couple of months the team reached a consistently steady pace of execution in the 45-50% load factor range, comparable to a BMW V6 engine sailing smoothly at 5000RPM.

There is one more key piece of data the burndown chart provides in this case. The amount of work in progress at any given time depicted by the yellow band after the reorganization is smaller than the 2x factor by which the size of the team was reduced would suggest as reasonable. It indicates that the new team is getting blocked less than the old team - people don’t have to abandon one work item in progress to pick up a new one because they are blocked. In fact, the very lean execution of the team after the reorganization would make any ScrumMaster really happy. Analysis of the team dynamics over the subsequent few months led to the following conclusions that explain this phenomenon:

- The team naturally abandoned creation of formal test plans. Instead, test plans were formulated during the sprint planning meeting and reflected in the work items planned for the sprint. As a result, testing was not blocked on the creation of test plans during the sprint.

- The team naturally abandoned creation of formal specifications and design documents for the purpose of feature hand off from development to testing. Whatever context needed to be conveyed was fleshed out during the sprint planning meeting, and complemented with ad hoc conversations throughout the sprint. Again, this enabled testing not to be blocked by lack of written specifications.

- Development and testing of a feature within the same sprint finally felt like a natural state of the world rather than artificially enforced constraint. This enabled the testing effort not to be blocked by the necessity to dust off historical technical context.

- Every team member developed skills and intuition related to both development and testing. This improved the efficiency of any cross-discipline discussion.

The reorganization also had a positive ripple effect on the shape of team’s processes that cannot be directly deduced from any of the SCRUM metrics. Since one group of people was responsible for both development and testing, testing became a tax on shipping software rather than an activity justified on its own. For a team of engineers keen on shipping more software, increasing efficiency of testing without compromising quality became a natural goal. Sizable up front investments were made in continuous integration and driving up the quality of the test bed. These resulted in huge reductions of ongoing cost of testing; the time it took to conduct a full test pass and analyze the results was reduced from close to a week to under one day. Driving up the quality of the test bed itself resulted in test pass rates increasing from rarely above 95% to rarely below 100% (and going the last 5% is always the most painful part of the road). As a result test failure analysis time was greatly reduced, as well as bug lifetime minimized. The same test framework was employed as a basis for functional, stress, and performance testing, which reduced the maintenance cost of the engineering systems. As a result, the 5 person team was able to continue servicing the legacy product created by the 10 person team, as well as continue adding new features. Interestingly enough, however, a team with 60% of testers and 40% of developers was found to be spending 60% of time on testing and 40% on development after the reorganization, despite being reduced by half in size.

The only disadvantage of the reorganization I can put my finger on has to do not with software engineering but with employee performance assessment. In software organizations that have performance appraisal systems aligned with engineering disciplines of testing and development, a job description that combines both is a struggle. Extra effort is required to recognize and meaningfully compare the effort of a software engineer against that of a developer or tester.

The transition from an organization with positions split along the testing and development discipline lines to an organization with a single position that combines both disciplines was a positive change. There was little to no incentive for any of the described improvements when the development and test teams were executing within their own, disparate charters, organization structures, and processes. What was particularly noteworthy in the reorganization is that many of the positive process changes happened naturally given the right set of initial conditions set by organization structure changes. For once software development and testing felt like smooth sailing rather than tacking against the wind.